Keeping Sámi weaving tradition alive

Background

The importance of duodji

The weaving of belts, shawls, shoelaces, bands and other garments is typical of traditional Sámi handicrafts, called duodji in the North Sámi language. Duodji is an essential part of the living culture of the Sámi, the indigenous peoples of Northern Europe who live in Norway, Sweden, Finland and North-West Russia.

The woven belt is an important element of the traditional Sámi dress called gákti. The style and decorative patterns of a gákti together with headwear, shoelaces and belt indicate a person’s Sámi identity and belonging to a particular local Sámi community. This is a non-verbal means of traditional communication, which shows great diversity of Sámi cultural heritage and is connected to the value of collectivity and traditional Sámi aesthetics.

The Sámi have used various kinds of leather belts, as well as twisted and woven wool belts. The woven belt called láhppeboagán requires special attention because this traditional weaving technique is threatened. This kind of woven belt has been used in the county of Finnmark in Northern Norway. This article is about the preservation of the weaving tradition of láhppeboagán in Kárášjohka (Karasjok).

The láhppeboagán belt is woven with a rigid heddle loom (njuikun) usually made of reindeer horn and a wooden shuttle (geahpa) with harness of wool and cotton (Picture 1). The belt consists of three parts: two woven edges (čuldojuvvon ravda) and a central woven section (guovddášgirji) (Picture 2). These parts are sewn together and reinforced with a supportive lining fabric (skoađas), which is usually a stiff sail fabric firm enough to hold itself up. The belt is made in cotton and wool.

Ann Solveig Nystad wearing her Sámi dress. Photo: RDM-SVD, Paula Rauhala.

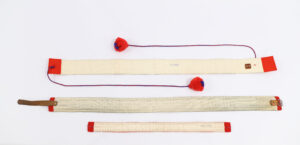

Traditionally the most common colours in woven belts are red, white and blue. However, nowadays various other colour combinations are used, mostly in machine-woven belts, following general innovations in the use of traditional Sámi dress. Both women and men can use the belt. A belt woven for children has a simple structure made of just one part, lacking the edge parts. Typical width for adults is about 5-7 cm while for children the width is approximately 3-4 cm (Picture 3, and Picture 4).

Weaving tradition under threat

This is an age-old and intricate way of weaving. Weaving requires preparing a harness by hand because essential materials with mandatory texture and colours cannot be purchased. This processing takes about three weeks and the weaving of one belt takes one more week. Today, there are few people knowledgeable about this tradition who weave belts for themselves and their families.

A rigid heddle loom (njuikun). Photo: RDM-SVD, Paula Rauhala.

Ann Solveig Nystad, a 59-year-old artisan living in Kárášjohka, is the youngest of ten people in the whole North Sámi area across national borders who weave láhppeboagán belts for sale using the traditional weaving technique (Picture 5). She is passionate about preserving this tradition and techniques, and she is encouraging people to learn and use it. The use of this technique is the best way to keep this unique weaving tradition alive. Because the whole process of belt weaving is time consuming, Ann-Solveig suggests that preparation of the materials could be done in advance for sale for artisans. If ready-to-use materials would be available to purchase, more people would probably start weaving.

The symbolism of the patterns in the woven belt represents Sámi worldview and philosophy. Descriptions of symbols in the belt might be specific for persons and families and can vary from one area to another. It is imperative to transfer this intangible heritage knowledge, which reveals interconnectedness of duodji, traditional pedagogy, family relations, identity and aesthetics.

Belt parts. Photo: RDM-SVD, Paula Rauhala.

The Sámi terminology connected to this weaving practise contains about thirty unique words describing the belt itself and its components, materials, tools, equipment and actions. The richness of the Sámi language might disappear if the duodji tradition of belt weaving by hand is not transferred to new generations. Additionally, it is a threat that because of the lack of knowledge about traditional terminology the language of the people using this technique will be simplified and lose valuable vocabulary. As a result, the history and understanding of this traditional practice may be lost.

Some Sámi artisans have started using new technologies and mechanical looms, producing woven belts of quite good quality (Picture 6). However, an expert in Sámi tradition with an eye towards weaving will recognize the difference between a hand-made belt and its machine-woven counterpart. Although the use of new technologies allows for the production of more belts, new technological solutions may quickly result in the disappearance of the intangible knowledge connected to the belt. Surprisingly, production of the machine-woven belts has contributed to unexpected results in Sámi society: the value and appreciation of the hand-made belts is rising. Subsequently, one can notice more interest towards weaving techniques among the Sámi. Hand-made belts have become increasingly fashionable in the communities.

The backside of the belts. Photo: RDM-SVD, Paula Rauhala.

Objectives

Safeguarding belt weaving requires raising awareness of the tradition in the first place. Artisans and cultural institutions, like our Museum, shall alert society about an urgent need to preserve and transmit this threatened weaving tradition to future generations. The more people will learn to master this technique and weave belts, the better it will be safeguarded. Knowledgeable artisans should be encouraged and supported to give courses in belt weaving. Good documentation of techniques and terminology is paramount for safeguarding this tradition.

Another side of safeguarding is the protection of the weaving tradition from misuse. Opening of free access to these techniques and patterns can result in cultural appropriation, commodification and commercialization for the benefit of non-Sámi society.

How it was done

Strategies and measures used in the safeguarding practice

The Sámi Museum has had a range of public activities to help to maintain duodji tradition, including weaving practices. These activities provide the local community with a sense of identity and continuity. Local practitioners help to run courses, transmitting their expert knowledge and skills. The Museum also displays exhibitions to enhance visibility of traditional crafts, which provide a platform for sharing ideas and experiences on traditional craft practices. Partnership between local public, educational and cultural-political institutions strengthen safeguarding efforts.

The Sámi Parliament of Norway has recently allocated funds to organize courses on the belt weaving technique. As a traditional knowledge holder and skilful artisan, Ann Solveig has taught several courses in belt weaving. She hopes that there will be followers who desire to continue this practice and will master weaving belts on a professional level. Thus, the weaving technique of láhppeboagán will be preserved for future generations. Preserving language is an important part of teaching weaving techniques. Therefore, teaching in the Sámi language is the way to safeguard and preserve this weaving tradition.

The use of Sámi terms and concepts in writing is one more strategy for knowledge dissemination. There are several books and booklets published in Sámi and other languages. Appreciation of the importance of indigenous concepts is shown in this article, where we present central traditional concepts and placenames in the Sámi language.

Top: a machine-woven belt, middle: a traditional woven belt; below: a child’s belt. Photo: RDM-SVD, Paula Rauhala.

The Sámi Museum has dedicated time and effort to document this unique weaving tradition. Ann Solveig has been engaged to make a detailed description of woven belts in the museum collection, which comprises about 50 items. In summer 2020 the Museums together with the Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association curated an exhibition about Sámi weaving. In addition to the museal representations of weaving techniques and woven products, a loom for weaving wool shawls was open for public use. A course in shawl weaving was announced, and a dozen locals took the opportunity to learn. This was an implementation of the “living museum” concept, which has shown to be supported by the locals and by the artisans themselves. Inspired by this successful practice, the Museum has started planning a belt weaving exhibition using the same model. Together with traditional knowledge holders, the Museum wishes to further develop the concept of living museum, implementing digital dissemination technologies to revitalize interest in belt weaving, raising awareness of the practice in society.

Additionally, the Museum continues collaboration with the Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association, which works with the Red List of traditional handicraft techniques that are little used, less known and visible, or forgotten. The aim is to add the Sámi belt weaving technique of láhppeboagán to the Red List. This List is not a finished index. Rather it is a project where local handicraft associations themselves choose which techniques from their own areas should be safeguarded, learned and documented. Adding to the Red List requires good documentation of the belt weaving technique. The Museum intends to document both the material and intangible cultural heritage of belt weaving and organize courses with Ann Solveig Nystad as a teacher. It is a collaborative practise of safeguarding, aiming to both document the weaving tradition and show the Museum’s visitors, especially locals, this unique traditional practice.