The Kven axe -revitalizing a tradition

Background

The Kvens have lived on the North Calotte for a long time. The first documented Kven settlement in Nord Troms is from 1522. In the 1700s and 1800s the Kven population increased markedly.

The Kven cultural heritage is an important part of our history, but one that is less visible in society today.

With the hope of protecting and passing on knowledge, Nord-Troms museum has developed a project focusing on an old Kven axe found in 1966.

Cultural heritage is a collective term for all material and intangible culture, which together form the historical basis for societies and ethnic groups. The cultural heritage is passed on by transferring objects, knowledge, beliefs and ways of acting from one generation to the next. For something to be described as cultural heritage, value or opinions must be added, and recognized as such by societies, groups and individuals (UNESCO, 2003). Intangible culture is vulnerable, as it, unlike objects, must be handed down orally or through practice. Action-based knowledge is embodied, the culture carrier and the knowledge are connected and inseparable.

Cultural heritage is important for group identity and continuity and promotes respect for cultural diversity. The national minority has been virtually invisible in public life in Norway, leaving cultural heritage to be continued in the private sphere, without separate archives and documentation as sources of information. The lack of focus and visibility has left Kven cultural heritage vulnerable, and in need of special protection of what we have left.

How it was done

In 2020, North Troms Museum received a request from the Kåfjord Kven Association asking if we could make a copy of an iron axe that had been found in Manndalen in Kåfjord – a so-called Kven axe. Through the project of reconstruction and contextualisation, we embraced both the material part of the object – the axe itself, and the intangible knowledge of how to make such an axe, how it is used and by whom.

This type of axe was common between 1500-1750, but may have originated as early as the 14th century. Our axe is probably from the 1700s. Four such axes have been found in North Troms, all in the Lyngenfjord area. The axe type is a special tool for a certain use; ry tømmer, debarking and working the timber for building log houses. The term Kven axe shows that the tool’s design and style have been particularly linked to a group of people- the Kvens (Figenschou 2012).

The original axe. Photo: Nord Troms Museum

The terminology Kven axe was the main reason for the Kåfjord Kven Association when they requested the reconstruction of this type of axe. Such name-giving often develop over time. Often used first by other groups, and then being adopted by the group itself.

These axes have been called Kven axes in our area for hundreds of years. One example being the reference made to a Kven axe in a trial in Helgøy District Court in 1707 (Lindback 2021).

Kven axes have not been made to symbolize an ethnic or social belonging, but to complement a functional need. For example, the enforced blade/bit provides a good cutting angle and creates distance between hands and timber. When an axe type is created, certain characteristics of the axe are copied repeatedly. The craftsmen have probably been in the same type of environment, and through social and cultural learning, the kven axe has taken its form in the process between craftsman and material. (Figenschou 2012).

The fact that objects intended to fulfill practical purposes over time, develop symbolic and communicative meaning, is not uncommon. When the Kåfjord Kven Association now wants to use a Kven axe to symbolize Kven presence over a long period of time, the axe will have added value, being representative for a distinctive group of people, with their own traditions and cultural heritage.

Contextualization

We have taken a closer look at the place where the axe was found, Storvollen in Manndalen, North Troms. In the latter half of the 1700s there was a drastic population increase in the region, including Manndalen.

“The population in Lyngen parish was for some years especially increased by the poor Sámi and Kven, who settled there for the fisheries, the fjords being at a comfortable distance for this”. (Larssen s. 79).

Manndalen went from having two farms in 1745 to 25 farms in 1801.

The axe was found on what was the farm of Hans Eriksen and Marit Henriksdatter. This farm was relatively large. They grew grain, had a grinder and Marit made liquor out of the grain. It is said that this was only used at religious congregations as a coffee substitute. Marit’s grandfather had previously worked with blacksmithing in the area. The first registered blacksmith in the village, Karl Pedersen, lived on Hans and Marit’s farm in 1801.

The farms at the time would have had many buildings. Buildings for storing meat, fishing equipment, wood, etc, and it is likely the farm also had a forge.

The axe as a special tool for clearing timber and would have been valuable with the construction activity caused by the population growth and need for new farm buildings and houses.

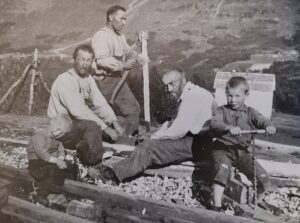

Housebuilding in Manndalen in the 1930s. Photo: Lisa Vangen

Axe shaft

The shaft of the axe is gone, but we know that axe shafts were shaped by use, axe type and personal preferences. Similar axe shafts found in Novgorod had an average length of 65 cm. (Figenschau 2012).

Nils Hansen, b. 1841 in Manndalen, taught his descendants a rhyme that was used in the family when making an axe shaft:

-Mihin menet?

-Metthään menen

-Mitä sinne?

-Vittan nouan

-Mitä sillä?

-Laiskan piiskkan

It means something like; Where are you going? To the woods. What are you doing there? To get branches for a switch. What do you need the switch for? To spank the lazy. (Kven spelling by Agnes Eriksen).

The rhyme has been passed on orally in the family to this day. From the neighbouring village, Skibotn, such rhymes have also been used when measuring the length of axe shafts in production. Each line corresponds to a fist length on the axe shaft, i.e. 6 fists is a suitable length of the shaft. If a male fist has a “cross length” of about 11 cm, the axe length in Manndalen and Storfjord corresponds with the average axe shaft length in Novorod.

Nils Hansen’s great-grandparents were Marit Henriksdatter and Hans Eriksen.

Reconstruction

Our blacksmith forged the kven axe using similar methods and same type of tools that were used to produce axes in the 18th century and earlier.

The blacksmiths at work. Photo: Nord Troms Museum

To make it work, one must find out how such axes are composed, by how many parts, as well as the order and method of assembling the different parts. Different special utilities were forged to get the job done.

Watch a video of the blacksmith at work on the axe: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AOlqoANVWTE

The forging was done in a reconstructed forge with a traditional bellows and charcoal as a heat source. The bellows is a replica of an old bellows that Isak Seppälä brought with him from the Pajala area in the Torne Valley in 1865. Incidently, the name Seppälä comes from the word “seppä” -blacksmith. The ending -lä refers to the place where the blacksmith worked. Some of the coal used in the forging process was taken from a traditional charcoal kiln.

Making charcoal the traditional way Photo: Hans -Erik Olsen

Action-borne knowledge

Nord-Troms Museum was contacted to make a copy of the kven axe, since we have the expertise and facilities to carry out such a task. At one of our facilities, we have a reconstructed forge with forge, anvil, and other equipment. But most importantly, our craftsman has acquired considerable blacksmithing expertise, as forging an axe is a complex process. The result depends on experience, material, knowledge and the coordination between head and hand.

Forging involves more than transforming material. The blacksmith puts his own mark on the product (Figenschau 2012). In this project, an assistant blacksmith has also been used, which was common in earlier times.

The process of forging an axe contains a lot of intangible cultural knowledge. In particular, the hardening process in which the tool becomes a cutting tool is important, magical and mythical. Before you began the hardening, the blacksmith had to be rested and focused. Some read powerful words to the north before the process started. What sort of tempering was used and knowledge of temperature was important.

Detail from the process. Photo: Nord Troms Museum

Strangers were chased out of the forge, and the lighting during work was important. Knowledge of such prerequisites for a good result often passed on from father to son.

The axe that we have reconstructed is therefore not an actual copy of the kven axe found in the potato field in 1966, for our axe copies bear the mark of the personality, preferences, knowledge and characteristics of our blacksmiths. But it is part of the category kven axe, and is made in the same way that all other such axes have been made for several hundred years – through imitation, trial and error.

Summary and future plans

As we have seen, the forging process itself is intangible culture, with use of resources, material and understanding the tools. There is also a lot of other knowledge related to this process, such as the use of phrases, rituals and “know-how”.

In the future the kven axe will help to recreate further intangible knowledge through use. Several copies of the kven axe have been forged and are now in use for timbering and other traditional construction techniques. Craftsmen get accustomed to working with this axe. Knowledge and skills are stored in heads and hands.

For Nord-Troms Museum, it is important to disseminate and pass on knowledge of forging as traditional knowledge. Exposure and handing down immaterial cultural heritage must be done through practice and documentation. We hold regular courses, but would like to have resources for an even greater focus on passing on the skills and knowledge to the next generation.

Crafts using your hands take time to learn. In addition to the technical skills, the knowledge must be memorised through exercise and repetition before it comes automatically. And after that, it must be practiced regularly.

The finished axes. Photo: Nord Troms Museum

We hope that through this project we have contributed to safeguarding a small part of Kven cultural heritage. And we have contributed in keeping the knowledge about long-standing interactions between nature, economy, history, social and cultural factors that this axe represents, alive.

The museum will now start a new project: a reconstruction of a traditional boat house from the 1800s. Birch will be used for the construction. The construction is “stavline med laftede røst”, a combination of stav and timber log. The project will contribute in safeguarding regional traditions and transmit traditional knowledge. Traditional materials and tools will be used in the project, including the kven axe.

An old boat house of the type that will be reconstructed. Photo: Nord Troms Museum