The triangle of craftsmanship – Safeguarding action-borne knowledge

Background

Main photo: Mile-burning of Pacific oysters, transforming an environmental problem, the invading Pacific oyster, to an asset for building heritage conservation and arts. The lime extracted from the shells in this process is very pure and will be tested as an alternative lime source for church restorations and arts (fresco and stucco lustro). Photo: Kjetil Storeheier Norheim, Norwegian Crafts Institute.

Passing on traditional crafts

The traditional expertise of basket makers, blacksmiths and ski makers is an important part of our heritage and needs as much safeguarding as do old textiles and farmhouses. But how do we best preserve living traditions like the age-old knowledge of carpenters and handweavers ?

In many respects, safeguarding tangible items is straightforward, for instance we can store old craft tools in magazines with optimized temperature and humidity. For intangible cultural heritage such as traditional crafts, however, these are defined as practices in the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, and as such are always a part of us as individuals. Often described as embodied, tacit, or action-borne knowledge, this expertise resides in the practitioner of the traditional craft, and needless to say we cannot preserve it simply by locking the bearer into a magazine. As the convention suggests this knowledge is “passed on from generation to generation”.

Action-borne knowledge

Passing on traditional crafts to new generations has been the core of the work of the Norwegian Crafts Institute for more than 30 years.

A cornerstone in our work is the concept of action-borne knowledge. We use the term to describe how the knowledge of a craft lies in the action and practice. The term also describes well how the craft is handed down from generation to generation.

It is defined as follows:

Action-borne knowledge is the sum of experience and knowledge that, in the form of skills, patterns of action and perception, is inherited from one generation to another in a knowledge-bearing action community. When transferring action-borne knowledge, the basic form of learning is imitation combined with testing and personal experience…

Action-borne knowledge requires direct person-to-person transmission. You can only acquire this knowledge by participating, just like learning a language. We can compare this process with, for example, sports and music. A folk musician plays by following the traditions of past folk musicians, thus learning by imitating a master. The knowledge is deeply ingrained in the mind and body of both the folk musician and the craftsman.

Picture showing the tradition of fishing for lågåsild (Coregonus albula) in the river Lågen close to Lillehammer, Norway. Photo: Tore Tøndervold, Norwegian Crafts Institute

How it was done

The triangle model for passing on action-borne knowledge

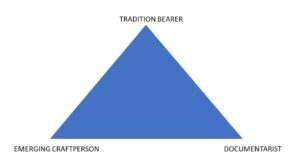

The Norwegian Crafts Institute quickly recognized the urgent need to safeguard many trades, crafts, and techniques. The expertise of potentially the last craftsmen in a particular trade, craft or technique is akin to a “burning library”. In response to this pressing challenge, the Norwegian Crafts Institute launched its first documentation and training projects in 1988. Since then, a model for perpetuating action-borne knowledge has been developed and cultivated through fieldwork and practical experience. The model can be described as a triangular model, comprising three key participants: the tradition bearer, the emerging craftsperson, and the documentarist/observer:

In this model, the tradition bearer, who embodies the knowledge, is the most important. The objective is to pass on this person’s knowledge. The emerging craftsperson is the primary medium for documentation medium. Through their own practice of the craft they will pass on the knowledge of the tradition bearer. In addition, the documentarist or observer chronicles the entire work process using video, images and text. The documentarist acts as a “fly on the wall”, capturing everything that takes place without intruding on the learning dynamic between the tradition bearer and the emerging craftsperson.

To make a complete documentation using this approach, the documentarist must have a deep understanding of the craft – the documentarist must be in the craft. The work process serves as the script or storyboard for the documentation. While this documentation primarily aids the new craftsperson, enabling them to repeat what has been learned even after the tradition bearer is no longer available, it also serves as a lasting record of the craft for future generations. Since much of the knowledge of the craft is embedded “in the body” – in movement patterns, hand techniques, work organization and other physical approaches – film or video is particularly important as a documentation medium. Though film and video can never replace direct training, it can serve as a valuable “memorabilia” for those who have received hands-on training in the past.

The triangular model is based on the age-old master-apprentice dynamic. Both the tradition bearer and the new craftsman are essential for the continuation of action-borne knowledge. For optimal learning of this action-borne knowledge, a one-on-one relationship has proven most effective, with the tradition bearer playing the most important role. This person not only embodies traditional knowledge, but also carries an abundance of experienced knowledge. Essentially, the tradition bearer merges traditions and knowledge from past generations with their own expertise. Each tradition bearer must be understood in light of the knowledge they represent. This often means that the traditions they hold are specific to a particular geographical area. For the Norwegian Crafts Institute it is therefore also important that such traditions continue to flourish in the area where they belong.

Focus on the process

In traditional craftsmanship and craft pedagogy, learning processes prioritize both the process and the outcome. In a training situation, those learning the craft often make the mistake of concentrating on the end product far too early in the process. Their focus is on the final creation, rather than observing the movement patterns, work organization and techniques of the person making the product. For apprentices, shifting their focus from product to process is essential.

Making reed shoes. Photo: Norwegian Crafts Institute.

Ice sawing-passing on a craft

A good example of a “five to twelve” safeguarding project is a project from 2007, where the tradition bearer Karl Garder passed on the technique of ice sawing (cutting large blocks of ice from frozen lakes and rivers) to the new craftsperson Thomas Orderud. Ice blocks were traditionally used for food preservation (cooling), and the technique largely went out of use as refrigerators and freezers came to the market. Karl Garder was one of the last persons in Norway that knew how to set up the traditional ice saw and used the traditional technique, and as he went into his 90’s it became urgent to pass the knowledge on to a new craftsperson. A project was established in collaboration with Follo Museum, the university colleges in Lillehammer and Østfold and the London Canal Museum, with Thomas Orderud as the new craftsperson. At first, the technique was passed on to Thomas at a 1:1 -level on lake Øyeren. Through this 1:1-relationship, Thomas acquired the skills and knowledge Karl was the bearer of throughout the project period, that ended with a gathering on lake Mjøsa in 2013. Since the project, Thomas has used his knowledge to build his own business, delivering ice blocks to snow and ice hotels and other ice projects throughout the Nordic countries. He also delivered ice to an ice rose produced and exhibited at the Royal castle for the 80th birthday of King Harald of Norway. During the project period 2007-2013, two “apprentices” from Hunderfossen Family Park also attended, who use ice blocks in their winter park experience on a yearly basis. This also ensured that the knowledge of Karl Garder can live on through more craftspersons, making the knowledge less vulnerable.

Watch a video showing the method of ice sawing here.

Decades of crafts projects. Reflections and recommendations

We have often encountered claims that a tradition is extinct, only later to discover through research that the tradition remains vibrant. It is therefore important to invest time in the field to maintain close ties with the community and craftpersons, to accurately identify and get an overview of living traditions. Using local newspapers and social media channels to find tradition bearers has also proven successful in many projects.

Sometimes tradition bearers may be hesitant to impart their knowledge. It may often be necessary to work with them over time to persuade them to share their expertise with the new craftsperson. Selecting the right craftsperson to carry on this knowledge is equally crucial for the success of the project. Ideally this should be a person from the same place or area as the tradition bearer, possessing both an interest and desire in learning the tradition and a capability to master and continue it. It is crucial that the chemistry between the traditionalist and the emerging craftsperson works. If there is a lack of chemistry between the parties, we have sometimes had to replace the craftsperson with a new one to bring the project forward.

We have also had projects with more than one craftsperson. While this approach may work well in some cases, we have observed that some tradition bearers tend to identify and focus on the craftsperson they deem most suitable, and sideline the other one. The best results are therefore most often found in projects with just one new craftsperson.

As the Norwegian Crafts Institute has been operational for more than 30 years, it is important to keep in mind that it may be necessary to repeat past projects. A craftsperson who learned a technique, skill or trade from a tradition bearer tree decades ago may now be the sole bearer of that tradition, much like a “burning library” that needs protection.

In his thesis titled “Transmission of Crafts”, Eivind Falk, head of the Norwegian Crafts Institute points out that “Action-borne knowledge is best transferred in an active, knowledge-bearing environment, such as a workplace.” Ideally, this transfer should take place in the tradition bearer’s own workshop, offering a familiar environment for the bearer.

Drawing from the Norwegian Crafts Institute’s extensive three-decade experience in the field, we find it fruitful to follow these five principles for safeguarding traditional crafts:

- Adopting master-apprentice model (1:1 knowledge transfer) is optimal.

- Knowledge transfer should ideally take place in the tradition bearer’s environment, in situ.

- Programmes should be carried out in collaboration with the broader community.

- Practical, hands-on approaches are crucial for effective transmission.

- Documentation has its merits, but the most important results come from the exchange between the tradition bearer and the learner.

References:

Falk, E (2018) Transmission of Crafts, Lillehammer: Inland Norway University of Applied Science.

Falk, Eivin Safeguarding a long willow flute, #HeritageAlive, ICHCAP

Kolle Grøndahl, Kirsti et al, (2016), Lenge leve tradisjonshåndverket!, Yrkesfaglig utvalg om immateriell kulturarv og verneverdige fag, Oslo: Utdanningsdirektoratet

Martinussen, Atle Ove (2007): Vidareføring av handlingsboren kunnskap, https://web.archive.org/web/20071016152622/http://maihaugen.no/templates/Page.aspx?id=6427

UNESCO (2003). Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention